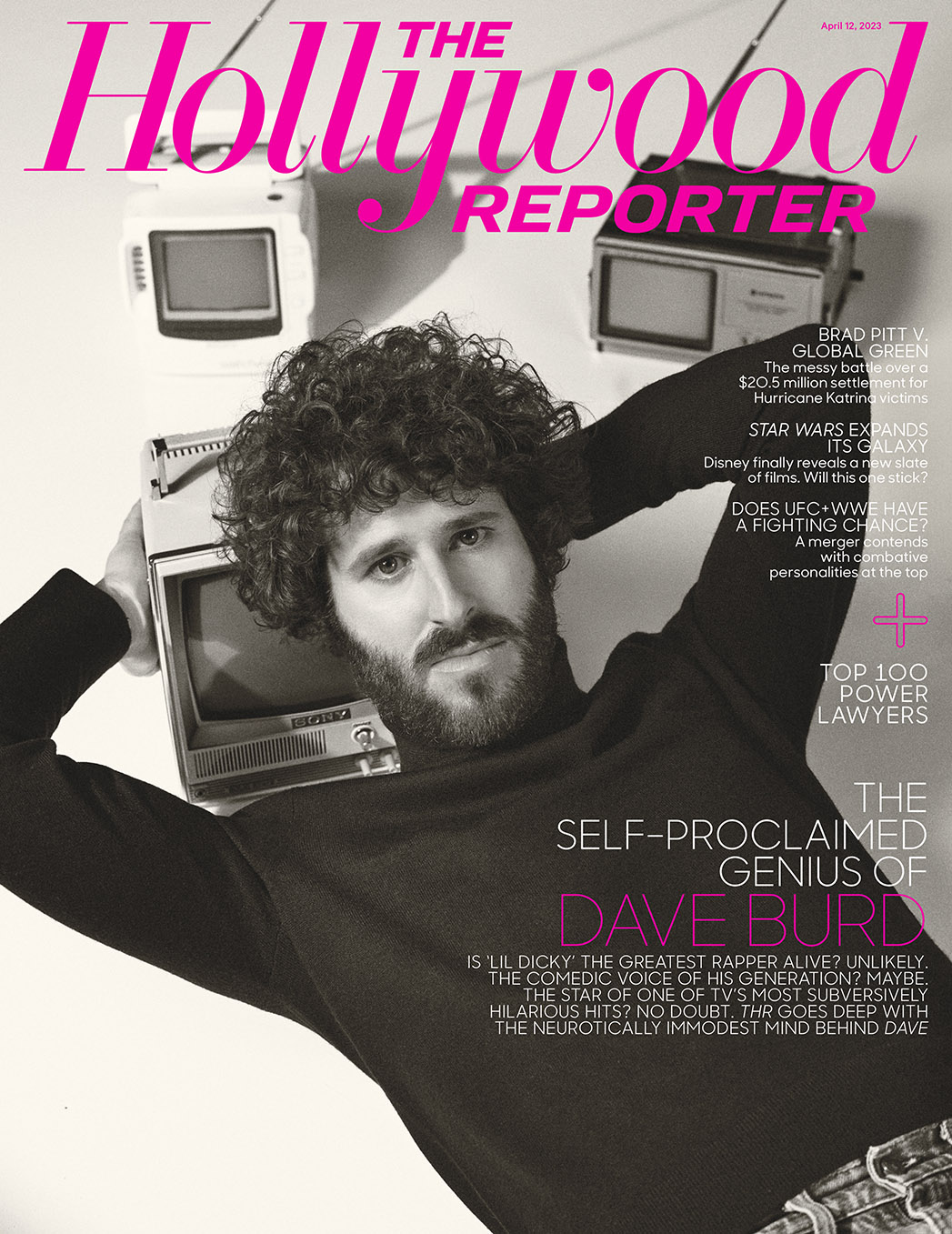

“I feel like I’m the comedic voice of my generation,” says Dave Burd before so much as our water glasses are filled.

Then he hesitates, recognizing how a declaration so seemingly hyperbolic might be interpreted. “You’ll read it and be like, ‘This guy’s out of his mind,’ ” he says, “and, really, I don’t mean it arrogantly.”

For the next several minutes, Burd, who performs under the stage name Lil Dicky, will attempt to delineate the difference between confidence and arrogance, an exercise that’s highly amusing in and of itself. “I’m not like, ‘Oh, I’m the fucking best rapper alive,’ or ‘I’m the funniest guy in the world,’ ” he tells me. “No, I’m more like, ‘I’m a passenger of this talent,’ and it’s funny to me that I happen to be born with these skill sets, and all I can do is be relentlessly responsible with them.”

Photographed by Austin Hargrave

At a bowling alley not far from Burd’s Venice Beach home, his venue selection for this early March evening, that soaring self-image is validated by a procession of superfans, who alternately stop, praise and gawk at him. At one point, a young guy overseeing the alley’s shoe exchange tells him that even his 80-something grandma could quote back an episode of Dave, Burd’s more-than-semi-autobiographical FX series that returned for its third season this month (until The Bear, its first season was the network’s most watched comedy). Burd stars as a neurotic narcissist named Dave, who performs as Lil Dicky and is certain that he — you guessed it — is destined to become one of the greatest entertainers of all time.

In real life, Burd has reached what he calls the “sweet spot” of fame. He’s largely able to move about the world, and yet he enjoys being approached periodically by fans who mostly offer adoration — and occasionally pepper him with questions about whether, as the TV show suggests, his penis really has two holes (spoiler: It does). If I weren’t with him, the 35-year-old would’ve engaged the woman who’d interrupted our post-bowling dinner to tell him about a freestyle rap course at Carnegie Mellon that includes a unit on his music; instead, he’ll try to remember to google it when he gets home.

Since Dave debuted in March 2020, just as the world went into lockdown, Burd has amassed an impressive stable of A-list fans, too. Madonna and LeBron James have publicly lauded the series, while others, like Chris Rock, Leonardo DiCaprio and Ben Stiller, have reached out privately. He and his fellow producers, who include manager Scooter Braun and comedian Kevin Hart, have managed to parlay that in-on-the-joke industry cachet into a string of buzzy cameos like Doja Cat, Don Cheadle, Justin Bieber and Lil Nas X. And though Burd’s reluctant to reveal who else will make appearances this season, he describes the final batch of guest stars as the “holy grail of iconicism.”

At the same time, he acknowledges, there are plenty of people who still have no idea who Lil Dicky or Dave Burd is. He’s certainly not so famous that he can’t go and enjoy himself at a bowling alley, which, it turns out, is also where he met Kristin, his girlfriend of three-plus years, whom he calls “the one.” Two frames into our game, he announces with staggering conviction that he’ll be bowling a 130 game this evening, which seems preposterously exact. But this is a guy who’s been making preposterous declarations his whole life.

***

Let’s get it out of the way: Burd was born with a condition called hypospadias, which means the opening of his urethra was not on the tip of his penis but rather on its underside. It entailed multiple corrective surgeries early in his childhood, and plenty of scarring, both physical and emotional. As his character describes the “very bizarre situation” more crudely in the opening scene of Dave, he’s had so much skin grafted down there, his “dick is made of balls.”

Another surgery was proposed when Burd was 14, this one to stop him from peeing out of two holes, but the recovery would have required that he walk around in a diaper for close to a year. “I was a freshman in high school,” he says, “and I was like, ‘Enough, I’m not doing it.’ ” His doctor’s advice to his therapist mom and teacher dad was simply to let it be. If there was an issue, their son would come to them; short of that, never bring it up again. From that day forward, his malfunctioning genitals became the family’s closely held secret, even if, as Burd acknowledges now, it informed every ounce of his personality.

“It was like other kids are starting to go to second or third base and I’m getting operations and they’re going wrong and oh my God, it’s the most top-of-mind thing ever,” he says, noting how he’d feign illness and need to go home at the suggestion of Spin the Bottle or any other attempts at intimacy. But it also never seemed to derail Burd’s confidence, certainly not his desire to get laughs. His camp talent show would end every summer with campers chanting, “We want Burd!” and he’d reliably deliver.

“This is just me theorizing, but I imagine if you have an insecurity the way that I did, you probably go out of your way to counter-set it with your strengths. So if I’m, like, bad at having a penis, what am I good at? Oh, making people laugh,” he reasons. “So maybe I cling to that even more if I’m an insecure person. Maybe I even create an identity around it and become the ultimate class clown, the guy who makes everyone laugh.”

Still, Burd never pursued comedy or theater in any formal way. Instead, he went to college at the University of Richmond, graduating a few years later with a business marketing degree and a cushy ad agency gig in San Francisco. He was moved into a creative role after wowing his bosses with an MP3 file of him rapping a status report on chip sales for the Doritos account. “It was the one email I’d send that would make it up to the partners, and I remember thinking, like, ‘I’ve got to show these people that I’m a star,’ ” he says of a scene he’s since fictionalized for the FX show. Outside the office, Burd was quietly building a library of comedic rap videos that he was funding with bar mitzvah money he’d stowed away. Once he had banked enough material, he would begin rolling them out weekly. As far as Burd could tell, there wouldn’t be much by way of competition, save for The Lonely Island, and his aspirations were considerably loftier.

On April 23, 2013, he dropped his first single, “Ex-Boyfriend.” In less than 24 hours, the song, a comedic take on the anxiety of learning about a girlfriend’s exceedingly attractive ex-boyfriend, had racked up more than 1 million views on YouTube. It was, and forever will be, the best day of Burd’s life — the day, he says, “where I realized I am who I always thought I was.” By day two, he was doling out interviews with TMZ from his cubicle. Within six months, he’d quit his job to pursue music full-time. His parents, who had urged him against the path, needed time to adjust.

“I was horrified,” recalls his mother, Jeanne Burd, by phone from Burd’s native Philadelphia. She and her husband were so taken aback by his decision to call himself Lil Dicky, they couldn’t initially process the subjects — from white privilege to premature ejaculation — that their son was rapping about. “We’d lived with his surgeries, and we’d kept it all so private his entire life, and here he was pulling it out for the world to see, and it was just a lot for us to take in. And then, yeah, we thought it was offensive.”

Their son, an upper-middle-class white Jew, was trying to break into a historically Black art form, and they worried, often with good reason, that “sometimes he can get lost in his own humor,” says his mother, “and he doesn’t always know how politically incorrect some of his thoughts might be.” Burd acknowledges that he didn’t have the same cultural awareness back then that he has today, which has developed in part with the help of Davionte “GaTa” Ganter, a Black rapper who became Burd’s hype man and his best friend. The pair met shortly before Lil Dicky’s first tour through an ex-manager and have been virtually inseparable since.

In that first meeting, Burd says, he was struck by how much he felt GaTa understood him as a rapper. GaTa, who’d worked with Tyga and Lil Wayne, was struck by Lil Dicky’s vulnerability, particularly within the hyper-masculine environment of rap. “There he was rapping about having this small penis and all his girl issues, where most rappers are talking about getting laid by four or five chicks a night,” he says, acknowledging that this has given him permission to be vulnerable about his own struggles, including his bipolar disorder. GaTa even allowed the latter to be depicted in a season one episode titled “Hype Man,” which was one of the most lauded and intensely powerful episodes that year.

By 2015, Lil Dicky was out with his debut album, Professional Rapper, which featured appearances by Snoop Dog, Fetty Wap, Rich Homie Quan and T-Pain. Initially, his fans, the “dickheads,” were largely young, white and male, though that evolved as his profile grew. The following year, he was posing alongside Lil Uzi Vert, 21 Savage and Lil Yachty for XXL‘s coveted Freshman cover. Rappers like Busta Rhymes and 50 Cent were telling him he was talented, and Kanye West had included him in a regular basketball game at his home. Hit songs and a series of viral videos with cameos including Ariana Grande, Ed Sheeran and Wiz Khalifa followed. There were plenty of haters, too, of course, and some ugly press, though to this day, Burd mostly writes it off as “elitist, hipster journalists who thought that it was their place to speak on behalf of hip-hop,” he says, “whereas I’m meeting the all-time great rappers and they’re telling me, like, man, I’m a rapper’s rapper.”

But rap stardom was never Burd’s end goal. As he told music producer Benny Blanco the first time the two met, “I’m just rapping to get a television show.” Blanco, who’s now one of Burd’s closest friends, still gets a kick out of the memory. There they were, at a Santa Monica coffee shop, when Burd, then little more than a viral comedy rapper, looked at Blanco, straight-faced, and laid out his plan: “He’s like, ‘I’m going to be the biggest rapper in the world, and I’m going to have the biggest TV show in the world, and I’m going to do this and I’m going to do that.’ And, of course, it all sounds so crazy at the time, but, like, he’s relentless, and he will. It’s all true. That’s the thing with him.” Back then, Burd’s parents weren’t so sure. Their son would come home between tour stops and routinely pose some variation on the question “If I put a gun to your head right now, would you say that I’m a creative genius?” His mother felt she needed to be straight with her son. “You’re funny,” Jeanne recalls saying, “but you’re no, like, Seinfeld.” Looking back now, she says the response would infuriate him; he says it motivated him.

Photographed by Austin Hargrave; Styling by Chloe Badawy; Banana Republic turtleneck, Levi’s jeans, Falke socks

***

Jeff Schaffer, who’d written on Seinfeld, already had his hands full showrunning Curb Your Enthusiasm when a friend asked that he take a meeting with Lil Dicky. He didn’t really have the bandwidth for a second TV show, but he was intrigued enough to say yes. Even in early 2017, Schaffer knew exactly who Lil Dicky was. “Back then, the internet was, like, 70 percent porn, 10 percent clickbait and 20 percent Lil Dicky videos,” he jokes, recounting how, at that first meeting, Burd told him he was going to be the biggest entertainer in the history of entertainment. “And I’m looking at this guy, and he looks like a piece of broccoli had a bar mitzvah, and I’m like, ‘This is hilarious, it’s like cartoon-level delusion.’ And then I start thinking, like, ‘What a great engine for a TV show, because what if he’s right?’ ”

Before long, the duo was off pitching a series all around town. It was the same thing every time: Burd would go in and start talking about how he’d always wanted to be a big comedy star, but then he’d started rapping and realized he was a really gifted rapper as well. “He would literally say, ‘It’s like if Batman all of a sudden realized he was also Superman,’ and when he’d say it, they’d all look at me and I’d go, ‘Yeeeaaah,’ ” says Schaffer, laughing now, just as he did then. “And, of course, they got the tone of the show immediately because they were meeting Dave.” (It should be noted that Burd is “very aware” of why the Batman and Superman line landed comedically, but he also wholeheartedly believes it to be true.)

HBO heard the pitch. So did Hulu, Netflix and Comedy Central. But FX offered a familiarity for Schaffer, who’d made The League there, and an impressive track record with comedies like Louie and Atlanta. Nick Grad, FX’s entertainment president, remembers being struck by the similarities between Burd and Burd’s hero, Larry David. “Very quickly, your radar goes up, and you’re like, ‘Oh, this guy’s interesting,’ ” he says. His only major note: The show shouldn’t start on the day Lil Dicky releases his first viral video, as the original pilot script called for. “He very wisely said, ‘Origin stories are sort of boring because we know what’s going to happen,’ and he was 100 percent right,” says Schaffer. “So we moved it six weeks later because six weeks later, you’re just a guy who had a viral video six weeks ago, you’re not legitimate, you’re not anything, and it’s a much more interesting place to start.”

Burd, who was overflowing with material —having taken notes at every tour stop for years — began filling out the cast. The only members of Burd’s inner circle who play themselves in the series are Blanco, who pops up periodically, and GaTa, who had never acted before but quickly became the heart of the show. Zooming from a makeup trailer in Australia, where he’s now filming a studio rom-com with Sydney Sweeney and Glen Powell, GaTa recalls the trippy process of having to audition for the role of himself.

“Dicky had, like, 20 audition tapes of GaTas. I was even getting text messages from my homies in the industry, like, ‘Yo, I’m auditioning to be you,’ and that shit tripped me out. It made me realize, ‘Hold on, Dicky’s like Phil Jackson or Steve Jobs, he just wants the best product.’ And FX doesn’t want to make me rich for no reason, I really got to be talented and funny and be able to move people,” he says. “But once I got the job, they’re like, ‘Forget what’s on paper, let’s just see what GaTa’s going to say today because we know it’s going to be funny.”

Burd saw the show as an opportunity to contextualize Lil Dicky’s often-controversial videos, or at least the man behind them. And to do that, he knew he needed to lay bare his deepest insecurities, which, of course, begin with his penis. He claims that piece has been freeing. “It had such a weight on my soul my whole life, and I just wanted to liberate myself and now I have,” he says. Still, given how much of himself he’s given over, it irks Burd and his network partners that there’s a perception, particularly among potential Emmy voters, that the series is just a protracted penis joke.

“The show is really not, like, fratty or bro-ey, and neither am I,” he insists. In fact, before Burd met Kristin, he was so desperate to settle down with a woman that he’d schedule a date per week; he even named his 2015 tour the Looking for Love Tour, and his 2016 one (Still) Looking for Love. (The former is also the name of his character’s tour on this season of the show, which typically trails his real life by five or six years.) He routinely texts his mom, just to say he’s thinking of her, and regularly tells his friends, male and female, how much he loves them. Burd and Blanco take their affection for each other a step further; they can be seen cuddling, naked, like nesting dolls, and showering together in a memorable season two episode that Burd says mirrors their real-life behavior. “It’s not in a sexual way, but truly, like, in a best friend way,” he says, telling me, “I wanted to put it out there because a lot of people related to it. And then, of course, there were others who were like, ‘What the fuck is that shit?’ “

Byron Cohen/FX

Schaffer believes the show works because Burd is so willing to put all facets of himself out there. “I literally call him a glass-bottom boat because it’s like you go for the ride and you get to see everything underneath. There’s body-image stuff, masculinity stuff, appropriation stuff — there are all these things that are so charged, and to his credit he wants to go right at them while also making a show that’s funny as fuck,” says Schaffer. As Burd sees it, the two aren’t, or shouldn’t be, mutually exclusive: “I think you can be emotionally poignant and nuanced and make a really sensitive, smart show while still thinking a dick joke is hilarious.” To that end, he’s as proud of a powerful scene that has his character being accused of exploiting GaTa’s Blackness during a heated segment of the radio show The Breakfast Club with Charlamagne Tha God as he is of a scene where his character loses control of his bowels during a hike. In fact, only the latter entailed a battle with FX executives — who occasionally worry that Burd is needlessly alienating those who dismiss the show as sophomoric — prompting multiple meetings, emails and pages upon pages of notes on fecal matter.

It’s his dedication to those seemingly tonal contradictions that drew Honey Boy director Alma Har’el, who signed on to direct Dave‘s second-season finale. What impressed her once she arrived on set was just how committed Burd is to every aspect of production. He had wanted to open her episode with his character trying to promote his album strapped to a billboard in downtown L.A. in only his underwear, but no one comes to see him because Ariana Grande has dropped an album the same day. “We get to downtown L.A. on a beautiful day. Out of nowhere, the sky rumbles and rain pours on us. Within minutes, it turns into sleet and then hailstones. Dave stands there in his underwear as everyone runs for cover and screams, ‘Keep shooting! Keep shooting!’ Because of safety reasons, the crew and all the equipment were covered and moved within minutes, but I stayed out and filmed it on my phone,” Har’el shares via email, adding: “In the finale, I used my phone footage as if it’s Benny filming Dave. It was a moment that really captured who Dave is and the lengths that he goes to in search of everything he’s chasing.”

It’s the kind of story you hear a lot of with Burd, a mix of relentlessness and ambition. Blanco insists he’s collaborated with more artists than he can count, and he’s never seen a human being work as hard as Burd. “Not only is he writing the show, he’s sitting there being like, ‘Is this the right camera angle?’ ‘How about this?’ ‘How about this?’ ‘How about this?’ He calls it the ‘no stone unturned method,’ ” says Blanco. “And of course, while he’s doing it, you’re like, ‘I’m going to kill you,’ but then you also feel that you are part of something bigger, something that’s going to be remembered.” Schaffer likes to say Burd’s tombstone will one day read, “Turn me over.”

Byron Cohen/FX

***

When Burd and I connect again a few weeks later, he’s just sneezed and thrown his back out. It’s forced him horizontal, which is how he’s now editing the show’s third season, a task that has consumed him 10 hours a day, seven days a week for months. He wishes he were further along than he is, but that’s only because he’s so immensely proud of the season — decidedly lighter and funnier than the last — and so desperately wants to release it into the world.

The major guest stars, who appear at the end of the season, are there because Burd wrote impassioned letters and logged long phone calls, even as collaborators told him he was crazy even to try. When they said yes, Schaffer admits he was reminded of a lesson that he clearly hadn’t learned yet: “Don’t doubt Dave Burd.” After what he’s managed to pull off, Burd tells me he no longer even bothers to ask his parents whether they think he’s a creative genius: “I really think what I’ve achieved this season renders the question null.” (For the record, Jeanne says she came around shortly after the show debuted and has told her son as much many times.)

Byron Cohen/FX

When Burd is done editing, he intends to get back to recording music. I ask him to put a timeline on that long-gestating second album, which he’s contractually obligated to deliver to BMG, but he’s been promising new music for so long that even he acknowledges he’s lost credibility with his predictions. “They’ll get one eventually, and they’re going to make a lot of money when they do,” he says. “It’s just been harder for me to convey my perspective via music. It’s a lot easier to be like, ‘What am I going to make episodes about?’ ” What he is certain of is that whenever the second album is ready, it will be much less comedic in nature. So much of what he’d produced before just makes him cringe now.

“I think, with his music, he was doing things to try to grab people’s attention, but the TV show actually got our attention,” says Charlamagne Tha God, who admits he’d been skeptical of Lil Dicky, the rapper, as he initially is of all white rappers. “I never heard people say, ‘Oh man, Dicky’s dope,’ he never infiltrated the culture, musically, like a Mac Miller or Eminem did, but with the TV show, 100 percent I heard that from the beginning. It’s all ‘Man, Dave‘s hilarious.’ I mean, you even have people saying Dave‘s better than Atlanta.”

In recent years, Burd acknowledges he’s been reassessing a lot of his early rap material and its impact, just as his character will later on this season. “It’s like you make these songs behind a computer, then you got to get onstage and perform them, and there’ve been times when I’ve been up there doing a comedic rap song and I can see in peoples’ eyes that they think it’s funny for a different reason, and suddenly I’m feeling all fucking guilty,” he says, citing one of his more controversial songs, 2013’s “White Dude,” which was all about how much more awesome it is to be a white dude than, say, a woman or person of color. Burd has since had its video scrubbed from the internet, and he’ll no longer perform the song. “I stopped because I was just like, ‘This is a crowd full of white men, and I know a good amount of them got the joke, but there’s just like those 10 super-drunk guys in the front row, and I can just see that they didn’t, and then I’ll get comments after the show, like, ‘Man, you’re better than the Black rappers.’ And I’m like, ‘Whoa. What the fuck are you talking about?’ ”

Stephen J. Cohen/Getty Images

He makes no apology for the 2018 track “Freaky Friday,” however, a collaboration with Chris Brown that’s arguably even more controversial. In that video, the two swap bodies, leaving Brown, who has a history of domestic violence accusations, singing about the blissfulness of anonymity and not being judged for his past, while Burd’s enjoying a newly luxe lifestyle and jubilantly dropping the N-word (it’s Brown actually saying it). As Burd tells it now, he’d always wanted to do a body switch song, and, specifically, he wanted to be “in the body of a really good-looking person who could sing and dance, and it’s not like I had infinite relationships back then,” he says. Around that time, Burd had been invited to be part of a celebrity basketball game, and he’d come early to warm up when Brown arrived. “He walks right up to me, and he says, ‘Hey man, I just want you to know, you’re an incredible rapper.’ And Chris Brown was my ringtone in the ninth grade, and it was just a very meaningful thing for someone to say to me at that time, and we kept in touch, and then we made that song, and I love that song. I still love that song. It went to No. 1 in multiple nations, and without that song, I don’t know that I could have made [a charity single] like ‘Earth,’ where I raised, like, $3 million [to fight against climate change].”

Burd takes a minute, presumably to think about what he’s just said, and then he keeps going. “I know that my heart is good. I really do. I don’t lose sleep at night about my heart. And you can never be perfect and sometimes I’ll still be dumb and unaware, but I really do care so much about doing the right thing,” he says. “And listen, I get why someone wouldn’t like a Lil Dicky song, but I’d never be OK with someone being like, ‘That guy’s an asshole,’ or ‘That guy’s a piece of shit.’ I’ve never had that experience as Dave Burd, the man, so for my art to cause that reaction, my God, it really hurts me.”

In the coming months, when Burd’s not focused on music, he’ll aim to finish the screenplay that he’s been noodling on for years. While he won’t give too much away, it too will borrow from his life, though he plans to focus more squarely on his childhood. As for other opportunities, he says he’s been turning down much of what’s come his way. “I’m not going to play, like, the comedic side character in a shitty comedy. I want to be in things that are up for best picture discussion, or I want to make my own revolutionary comedy or drama,” he says, rattling off inspirations like the Coen brothers, the Safdie brothers and Paul Thomas Anderson. “I mean, I named my production company Gr8 Films because I want to be synonymous with the best level of art.”

It all sounds so absurdly self-aggrandizing, but as I stood beside him at the bowling alley, surrounded by his fans, he delivered that 130 game he’d told me he would, a reminder that Burd should not be so easily dismissed.

This story first appeared in the April 12 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.